Decades of hardship have left parts of Oldham town centre in a derelict state.

Run down buildings with more weeds than windows tower over Union Street, and a once-buzzing Yorkshire St is now dominated by shuttered storefronts and closed restaurants.

But all that could be about to change. A huge new project aims to bring 2,000 homes to Oldham – bringing people right to the heart of the town centre, with the high street and Spindles shopping centre right on their doorstep.

A consultation is underway with local residents about the project, which is led by Oldham Council and the ‘city developer’ Muse.

The plans currently propose a series of apartment blocks arranged around green spaces and courtyards on disused sites (known as ‘brownfield sites’). These include the demolished Magistrates Court and the current Civic Centre, with the council chambers due to be moved to the Old Library on Greaves Street.

Similar to Muse’s projects in Manchester’s Northern Quarter and Salford, the blocks will contain a mixture of housing and spaces for cafés, restaurants and shops as well as amenities like nurseries and gyms.

And they’ll form part of a new plan for five ‘character areas’ across the town centre, including a ‘cultural quarter’ and an ‘education quarter’.

Like other towns, Oldham has seen its high street decline over the last decade. The town is also in the midst of a housing crisis, with more than 7,000 people currently on Oldham’s social housing register, demand far outstripping the local authority’s supply.

Council leader Arooj Shah and CEO of Muse North West, Phil Marsden told the MEN they believe their ten year plan and 15-year partnership will be a turning point for Oldhamers.

So, how do you transform a derelict town?

Create new neighbourhoods and new communities

“It has to benefit the people of Oldham,” Coun Shah said, speaking to us from councillors’ headquarters in the Oldham Civic Centre.

Under the new plans, these offices could soon be reduced to rubble. They would be demolished along with the brutalistic Queen Elizabeth Hall, which contains unsafe Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (RAAC) concrete, to make way for a completely new neighbourhood.

Only the Civic Centre’s ‘landmark’ tower would be retained and turned into a hotel.

“It’s not just about homes,” Shah went on. “We want to build communities where there’s leisure, there’s really nice restaurants and where there’s activity and people will want to build and raise their families here.

“What we’re trying to do is break the mould and really transform the town centre in a way that’s innovative. The only other places that have done it are leading cities.”

The plans re-organise the town centre on a large scale, incorporating everything from nature-based play areas to ambitions for a new heating network powered by abandoned mineshafts underneath the city.

For example, Oldham Mumps, currently a vast and underused car park wasteland, would become an energy centre and a new residential complex under the plans.

Make high streets a part of the community

Housing is nonetheless at the heart of the scheme. The Muse homes will be a mix of social homes, affordable rent schemes, shared ownership, affordable housing and private homes, providing ‘entry points’ for ‘all kinds of people’ according to Muse CEO Phil Marsden.

Bringing residents closer to the centre instead of concentrating them in residential suburbs means it will be easier for them to get to the shops, restaurants or gyms in town, Shah noted. This in turn could boost town centre businesses, many of which are currently struggling.

“Shops need people,” Marsden said. “In this day and age [shops] need to be accessible. It needs to be on our doorstep.

“It’s about putting the right retail back in and leisure back in and putting the people alongside that.”

Both bosses argued the way that people shop has ‘changed’ as a result of online shopping and habits picked up during the pandemic. The town centre needs to ‘reflect that change’ with retail options that are ‘even more convenient than the tap of a thumb’.

Value what you already have

Marsden was born and raised in Oldham, and though he prefers to keep his developer hat on, Marsden admitted the project is ‘personal’ to him.

“I can’t walk into a pub in Oldham without bumping into a cousin,” he said. “And the first thing they say is ‘when’s it gonna happen’?”

To him, the project is ‘as much about aspiration for Oldham people’ as it is about redesigning the town. Phil said: “I think sometimes because the conditions haven’t necessarily been right, the aspiration leaves the town and heads down the M62 into Manchester”.

He believes making the conditions right in the town would entice more of Oldham’s talent to stay and invest in their hometown. But he added that people tended to overlook the many plus sides the town already has.

Marsden said: “If I take away the personal stuff. If I make it really cold and factual… If somebody said to you – there’s this place that is right on the doorstep to some of the most stunning countryside in the country.

“It’s got a mass transit system that links it to one of the fastest growing cities in Europe with the best universities. It’s got one of the youngest, most vibrant populations. It’s got a community that really, really cares and it sits in a region with probably some of the most devolved powers outside of London. Do you fancy investing in it?

“You’d say yes.”

“In the past, [investments into Oldham have] been a little bit tainted towards ‘in need of’ – begging bowl kind of stuff. But actually, Oldham’s worthy of it. Sometimes we need to remind people of what we’ve got here.”

Use ‘brownfield’ land first and create more green space

And what Oldham’s definitely got is plenty of brownfield sites. That’s land that has been used for development before, in contrast to greenfield land which has never been built on and is usually used for farming or green space.

All of the sites chosen for the project are brownfield. They include the land from the old leisure centre on St Mary’s Way, demolished in 2016, and the former Magistrates Court, knocked down in 2019.

Manchester Chambers (West St), Henshaw house (Market Place) and a number of Oldham’s overabundant car parks (Prince’s Gate, Waterloo St, Southgate and Bradshaw St car parks) would be demolished as part of the plans too.

At the same time, the plans incorporate plenty of new green space, adding a new ‘Linear Park’ that runs the length of the town centre.

Shah said: “The minute you start talking about developing you hear ‘Don’t build on our greenbelt!’ so that’s why the brownfield first is so important. But people still need to be able to enjoy open and green spaces.”

Put locals first

The council boss admitted Phil’s Oldham heritage was part of what convinced her to enter the local authority into the 15-year partnership with Muse, which she described as a ‘sink or swim together’ arrangement.

“Phil’s Oldham roots mean that he has an understanding of what’s needed here,” she said.

Asked if she was worried about gentrification and Oldhamers being priced out of the area, she added: “People in Oldham deserve the best. I’ll be damned before I cater for anybody else before I cater for our own people.”

But she added: “We need to build public confidence. At a time when we’re having parallel conversations about fiscal challenges, if people in Oldham don’t look at something that’s happening in their community where they can point at it and say it’ll benefit them, then you’re doing the wrong thing.

“This isn’t something we’re planning to attract people who don’t live in Oldham to come and live here. If they do that’s fine but really it’s for local people to enjoy a space that’s going to be there for them.”

Find the money

But all dreams have their price. A number of plans have been put forward in the last years promising to ‘transform’ the town centre before falling through because of funding troubles.

Marsden noted that he’s experienced some scepticism from the Oldham public because past plans had fallen through.

Meanwhile Shah notes that the funding sources will be separate from Oldham’s current money troubles – which sees them fighting a potential £35m overspend in their day-to-day spending pot. Instead Muse say they will source the funding through capital markets, with investments from institutional investors, build to rent operators and housing providers.

The council will also be applying for external grant funding from central government, which has already been used to fund the project so far.

The plans (‘development framework’ in council-speak) are still under consultation and locals are encouraged to have their say online before September 11. The reviewed framework will then go to cabinet for approval in autumn, with final plans due to be submitted in early 2025.

If all goes smoothly with the planning application process, Muse are expecting to have spades in the ground by autumn 2025.

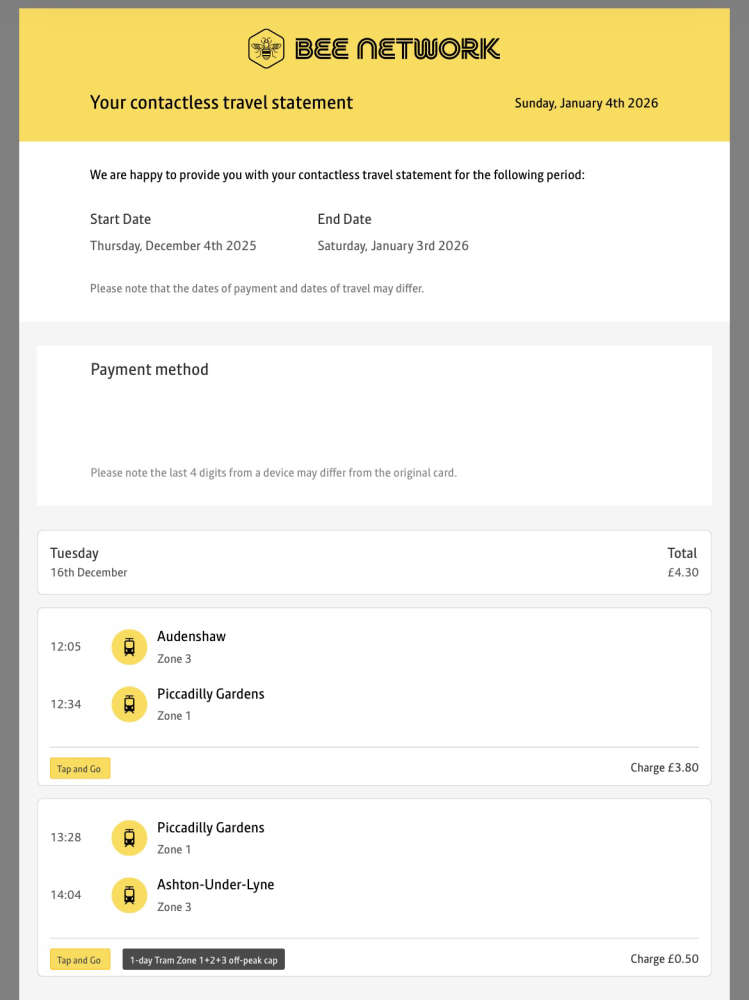

‘I was fined £60 by Metrolink after they said I paid in full – it’s just confusing’

‘I was fined £60 by Metrolink after they said I paid in full – it’s just confusing’

Willow Wood Hospice welcomes government commitment but calls for fairer funding

Willow Wood Hospice welcomes government commitment but calls for fairer funding

The Vale unveils early 2026 live music line-up

The Vale unveils early 2026 live music line-up

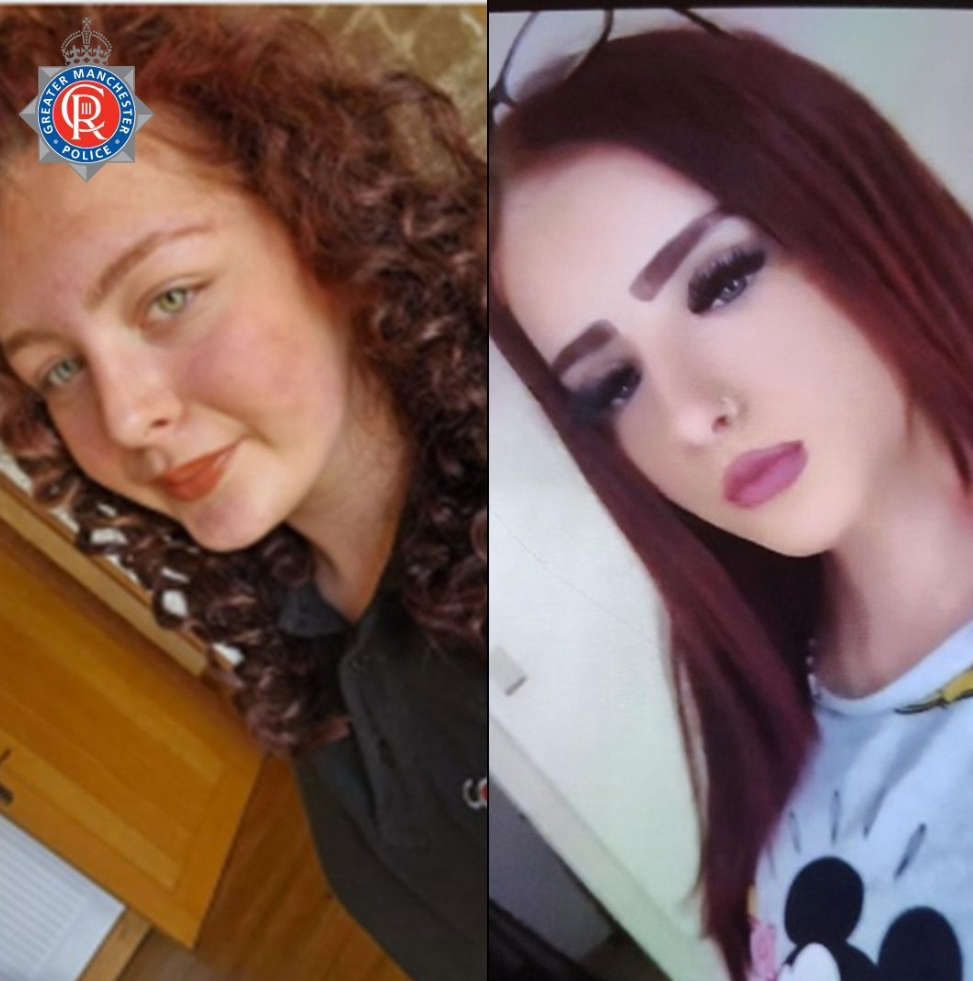

Police launch urgent appeal to find two missing girls

Police launch urgent appeal to find two missing girls