Tears of grief, joy, anger. Decades of pent up emotion came to the surface at an event to memorialise the almost 300 babies buried in a mass grave in Royton.

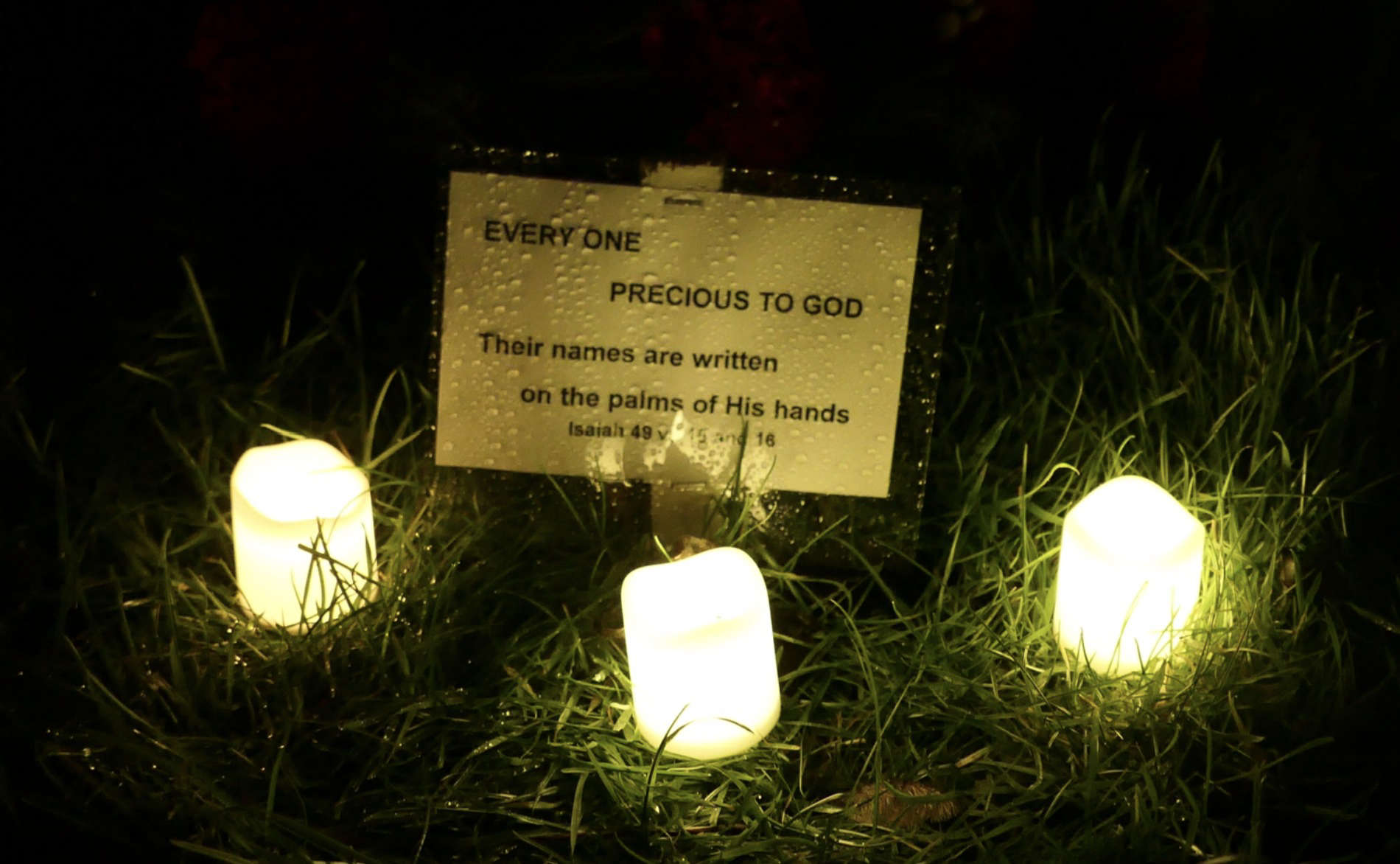

The church service at St Paul’s Church and candlelight vigil at Royton cemetery was to acknowledge a horrific practice that went on for years between the 50s and late 80s.

Stillborn children or babies who passed away shortly after death were removed from their parents and buried in unmarked mass graves – without their parents’ knowledge.

Many parents spent decades trying to locate the last resting place of their children and many went to the grave never knowing.

On Sunday some were able to finally honour their loved ones with a real service at St Paul’s, afterwards setting candles and flowers onto the approximately three by three metre plot in Royton cemetery.

One attendee was supporting her grandmother, whose sister was buried in the plot. Her grandmother, who didn’t wish to be named, is unwell.

“This is really meaningful to her,” her granddaughter said. “So we’re here today to support her.”

Marilyn Spence, a Hollinwood resident, described how her mother’s stillbirth in 1955 had hung over the family for as long her mum lived. She died never knowing where her lost son was buried.

“They just took the baby away – she never even got to hold him – and said they’d give him a Christian burial somewhere. Obviously we now know that wasn’t true.”

Marilyn recently traced the child to another communal plot in Hollinwood, where he’s buried with 23 others.

Asked what the service meant to her, Marilyn teared up. “It’s just lovely. They’ve never had anything. I just get so emotional for my mum’s sake.”

While some felt the event brought them a real moment of acknowledgement – others couldn’t help but feel angry that people were left in the dark for so long.

“The more I think about it, the more angry I get,” Gina Jacobs said. The momentum around the uncovering of stillborn babies in unmarked graves in many ways started with the 79-year-old turned activist.

Gina spent 53 years tracking down the grave of her baby son, until she found him two years ago in a mass grave in Landican cemetery, in the Wirral. Since then she has been helping others locate their lost loved ones.

She described similar plots she’s come across with hundreds of babies within them.

“Like landfill for babies,” she said. “It’s horrific. They did absolutely nothing wrong, except for being born sleeping. Yet they’re treated like murderers.”

She added: “I never would have dreamed of the scale of this when I started.”

A recent LBC investigation uncovered that 89,000 babies are buried in unmarked plots across the UK. And the data comes from just 45 of the 314 councils asked – meaning the true scale of the problem is likely much larger.

Maggie Hurley, who helped organise and fund the memorial event, believes the figures could even hit the million mark. She has called for greater transparency from local authorities and the government.

“This is a social injustice on a scale I never imagined,” she said. “In some ways we’ve been lucky here in Royton. All the relatives of the babies in this mass grave now know they’re there.

“But other mothers out there don’t. Royton today led the way, but the work needs to continue. This doesn’t end here.”

Coun Hurley believes the Royton discovery is just the ‘beginning of a movement’ and hopes to one day see a ‘national database’ where any relative can locate their lost child. Currently, many of the records – including some in Oldham – are not digitalised, but in physical ledgers that need to be manually checked.

“Relatives need to be able to find their babies,” Hurley said, adding that if local authorities weren’t able or willing to foot the bill – then the government would need to step in.

But even locally in Oldham, there is much left to do. At the candlelight vigil, one relative claimed to have discovered another mass grave on the other side of the cemetery – indicating that there may be more in the borough left to uncover.

Though the relative was too upset to speak out about the experience, Coun Hurley told the LDRS they’d discovered their son was buried in another unmarked plot along with several others. The grave was also honoured with a number of candles and a memorial wreath.

Meanwhile Marilyn, whose little brother is buried in Hollinwood, said the grave there was nothing more than a ‘mud patch’. She has called for a local memorial event in Hollinwood and hopes other relatives may come forward to connect with her.

And many bereaved family members are still looking for answers as to how the practice was allowed to happen – and why they were lied to for so long.

But as relatives took it in turns to place candles around a big selection of wreaths, flowers, balloons and teddy bears, it was clear the memorial service was already a big step in the right direction – with a community finally able to honour their dead with the love and respect they deserve.

Award-winning band strikes up a fitting tribute

Award-winning band strikes up a fitting tribute

Student making headlines with new shoe brand

Student making headlines with new shoe brand

Think! Fatal 4 Offences

Think! Fatal 4 Offences

Free football to counteract anti-social behaviour

Free football to counteract anti-social behaviour